Freedom comes at a cost, but conformity exacts an even greater toll. In Miloš Forman’s searing adaptation of Ken Kesey’s counterculture novel, the battle between individual liberty and institutional control plays out within the sterile confines of a mental institution, where the lines between sanity and madness blur with disturbing ease. Nearly five decades after its release, “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest” remains a devastating portrait of rebellion against authority and an enduring testament to the human spirit’s resilience in the face of systematic oppression.

Quick Summary Box

| Category | Details |

|---|---|

| Movie Name | One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest (1975) |

| Director | Miloš Forman |

| Cast | Jack Nicholson, Louise Fletcher, Will Sampson, Brad Dourif |

| Genre | Drama, Psychological |

| IMDb Rating | 8.7/10 ⭐ |

| Duration | 2h 13m |

| Where to Watch | HBO Max, Prime Video, Digital rental platforms |

| Release Date | November 19, 1975 |

Introduction: A Cultural Watershed

When “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest” arrived in theaters in 1975, America was still processing the social upheavals of the previous decade—civil rights battles, antiwar protests, and challenges to established authority. Miloš Forman, himself a Czech émigré who had fled communist oppression, brought a uniquely informed perspective to Ken Kesey’s 1962 novel, transforming it into a powerful cinematic statement about institutional power, mental health treatment, and the human cost of conformity.

Produced by Michael Douglas and featuring a cast that mixed established actors with real psychiatric patients, the film approached its subject with unprecedented authenticity. Forman insisted on shooting at Oregon State Hospital, an actual mental institution, creating an environment where the line between performance and reality often blurred. This commitment to verisimilitude, combined with Jack Nicholson’s iconic performance and Louise Fletcher’s chilling portrayal of Nurse Ratched, resulted in a film that swept the five major Academy Awards (Best Picture, Director, Actor, Actress, and Screenplay)—a feat only achieved twice before and once since.

Beyond its accolades, “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest” permanently altered public perception of mental healthcare institutions and sparked crucial conversations about treatment protocols, patient rights, and the very definitions of sanity and madness in a conformist society. Nearly five decades later, its examination of how power operates within closed systems remains as relevant and unsettling as ever.

Plot: Rebellion in the Asylum

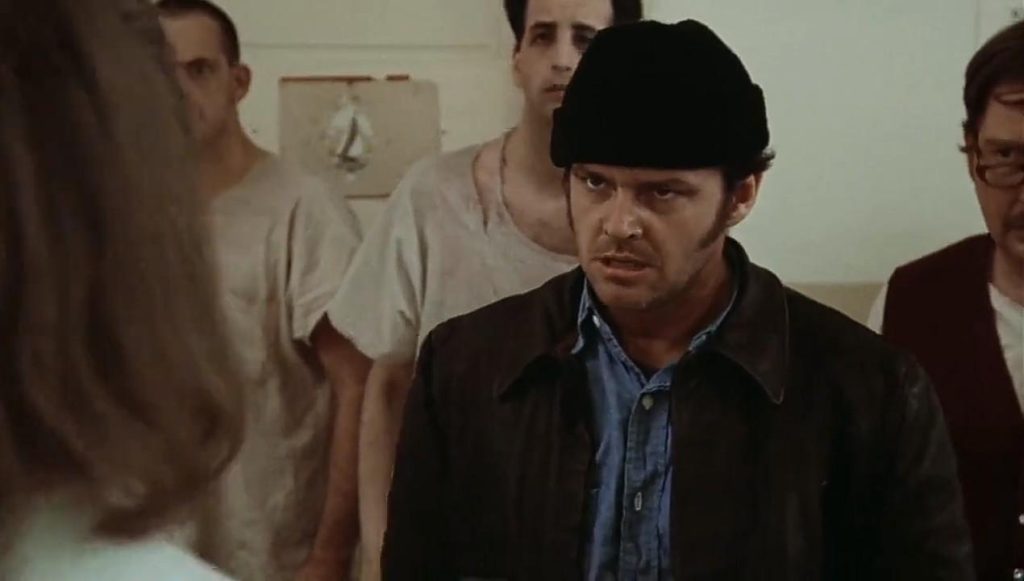

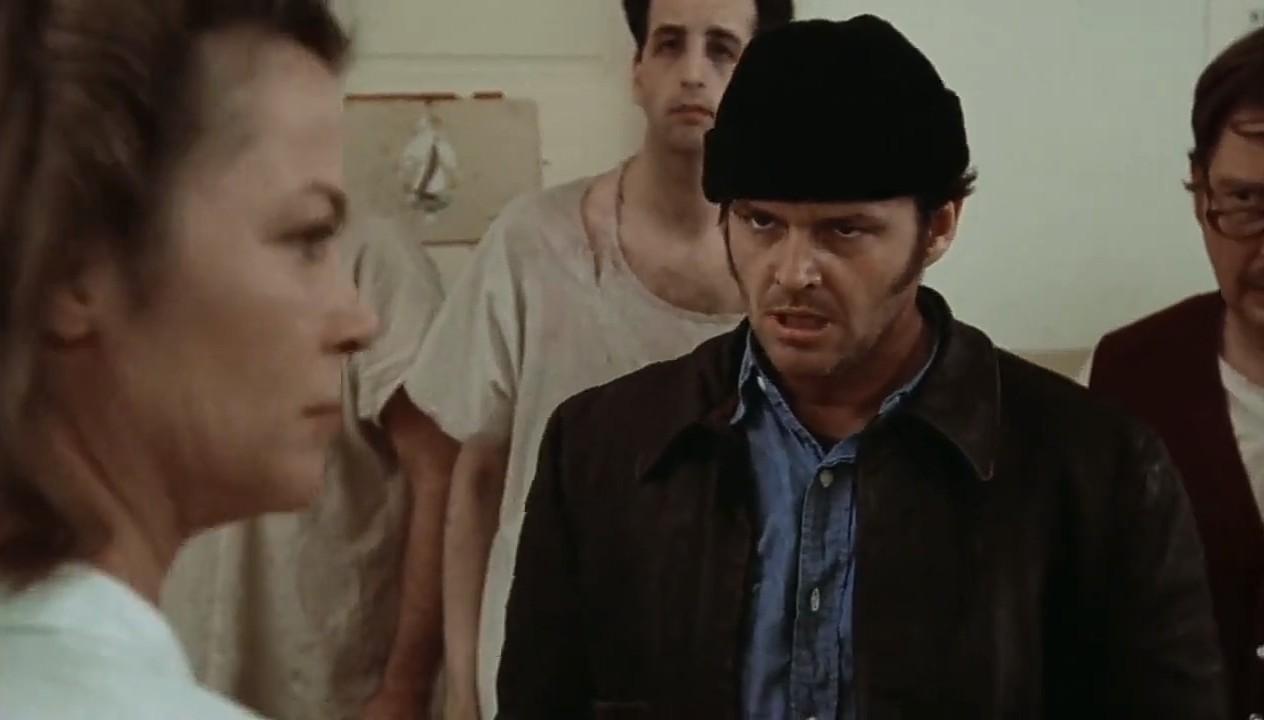

Randle Patrick McMurphy (Jack Nicholson), a free-spirited criminal serving time for statutory rape, feigns insanity to avoid prison labor and secure what he assumes will be an easier sentence in a mental institution. Upon arrival, he encounters a ward run with precise, dehumanizing efficiency by Nurse Ratched (Louise Fletcher), whose soft-spoken manner masks an iron-fisted control over her patients through medication, therapy sessions designed to reinforce feelings of inadequacy, and the omnipresent threat of electroshock treatment.

McMurphy’s fellow patients include the anxious, stuttering Billy Bibbit (Brad Dourif), the delusional Martini (Danny DeVito), the educated but unstable Harding (William Redfield), and the seemingly deaf and mute Native American “Chief” Bromden (Will Sampson). Most are voluntary commitments who have become institutionalized, accepting Ratched’s authority and their own limitations.

McMurphy’s natural rebelliousness—organizing card games, attempting to change the TV schedule so patients can watch the World Series, and eventually hijacking a bus to take everyone fishing—directly challenges Ratched’s control. His defiance inspires the other patients, particularly Chief Bromden, who eventually reveals to McMurphy that he can speak and hear, having feigned disability as a defense mechanism.

As McMurphy gradually realizes he cannot simply leave when his prison sentence ends—his fate now depends on the staff’s evaluation—his confrontations with Nurse Ratched escalate. After smuggling women and alcohol into the ward for a late-night party, McMurphy learns that young Billy Bibbit has committed suicide following Ratched’s threats to inform his mother about his sexual encounter during the party. In a rage, McMurphy attacks Ratched, attempting to strangle her.

For this final act of rebellion, McMurphy is subjected to a lobotomy that leaves him an empty shell of his former vibrant self. Chief Bromden, unwilling to see his friend reduced to this state, smothers McMurphy as an act of mercy, then demonstrates his newfound strength by tearing a water fountain from the floor and hurling it through a window to escape into the night.

Performance Analysis: Acting as Truth-Telling

“One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest” features one of the greatest ensemble casts in film history, with performances that feel less like acting and more like documentary truth.

Jack Nicholson delivers what may be the defining performance of his legendary career. His McMurphy is a complex contradiction—a selfish criminal who unwittingly becomes a liberator, a manipulator who ends up genuinely caring for his fellow patients. Nicholson’s physicality is crucial to the character, from his explosive laugh to his swaggering gait to the gradual dimming of his once-vibrant eyes. He embodies unrestrained life force itself—making his eventual lobotomy all the more devastating. The genius of Nicholson’s performance lies in how he balances McMurphy’s self-interest with emerging compassion, creating a flawed hero whose final sacrifice feels both inevitable and heartbreaking.

Louise Fletcher accomplishes the nearly impossible task of making Nurse Ratched a three-dimensional villain rather than a caricature. With her perfectly coiffed hair, spotless uniform, and soft, reasonable tone, Fletcher’s Ratched embodies institutional authority that wields control through procedures, medications, and paperwork rather than overt cruelty. What makes the performance so chilling is Fletcher’s suggestion that Ratched genuinely believes she’s helping her patients, even as she systematically breaks them down. The controlled placidity of her expression, breaking only momentarily after McMurphy’s attack, reveals a character who has sacrificed her own humanity to the system she represents.

Will Sampson’s Chief Bromden provides the film’s moral center and narrative perspective. Despite limited dialogue, Sampson conveys volumes through his eyes and physical presence. His transformation from a man pretending to be invisible to one who reclaims his power becomes the film’s most profound character arc, culminating in the iconic escape sequence that provides the story’s only moment of genuine liberation.

The supporting cast of patients delivers performances of remarkable authenticity, with many actors living on the hospital grounds during filming to better understand their characters. Brad Dourif’s Billy Bibbit, Sydney Lassick’s childlike Cheswick, and William Redfield’s intellectualizing Harding each embody different responses to institutional control, creating a microcosm of society within the ward.

Visual Storytelling: Confinement and Control

Miloš Forman and cinematographer Haskell Wexler (later replaced by Bill Butler) utilize visual language to reinforce the film’s themes of confinement and control. The ward’s sterile environment—with its white walls, fluorescent lighting, and geometric precision—becomes a character itself, the physical manifestation of the system’s dehumanizing effects.

The film’s composition frequently emphasizes power dynamics through framing. Nurse Ratched is often filmed from slightly below, enhancing her authority, while group therapy sessions are shot to highlight the patients’ vulnerability in the circle formation. The ward’s large windows, which should represent connection to the outside world, instead emphasize the patients’ separation from it.

Forman employs strategic shifts in visual style throughout the narrative. Early scenes establish a claustrophobic, controlled environment with steady, symmetrical framing. As McMurphy’s influence grows, the camera work becomes more dynamic, particularly during the fishing expedition sequence, where handheld shots and natural lighting create a visual respite from the ward’s artificial environment. The final act returns to rigid composition, but now the audience experiences it as oppressive rather than orderly, having been shown the possibility of freedom.

Sound design plays a crucial role as well. The ward’s ambient noise—keys jangling, intercoms buzzing, the mechanical hum of electrical equipment—creates a constant auditory reminder of institutional control. This contrasts sharply with scenes outside the ward, where natural sounds predominate, highlighting the sensory deprivation inherent in institutionalization.

Thematic Richness: Power and Rebellion

While superficially about mental illness, “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest” uses its setting to explore broader themes about society and human nature:

Institutional Control vs. Individual Freedom: The central conflict between McMurphy and Nurse Ratched represents the eternal tension between individual liberty and institutional authority. The film questions when order becomes oppression and when treatment becomes control, suggesting that systems designed to help often end up primarily serving their own perpetuation.

Definitions of Sanity: The film deliberately blurs the line between who is “sane” and “insane,” suggesting that these labels often have more to do with compliance to social norms than actual mental health. McMurphy’s “craziness” represents authentic self-expression, while the patients’ “sanity” often requires suppression of their true selves.

Emasculation and Reclaiming Power: The film explores how institutions feminize and infantilize men to control them. Nurse Ratched’s dominance over the male patients carries maternal overtones, with therapy sessions resembling scoldings and rewards systems treating grown men like children. The patients’ journey involves reclaiming their masculinity, though the film complicates this theme by acknowledging the problematic aspects of McMurphy’s brand of masculinity as well.

The Medicalization of Nonconformity: Through its portrayal of “voluntary” commitments for conditions like homosexuality (Harding) and social anxiety (Billy), the film critiques how mental health institutions have historically pathologized behaviors that merely deviate from social norms.

Cultural Genocide and Restoration: Chief Bromden’s storyline highlights the destruction of indigenous cultures by dominant white institutions. His feigned deaf-muteness symbolizes how native peoples were silenced, while his eventual reclamation of voice and freedom represents cultural resurrection and self-determination.

Cultural Impact: Changing Mental Healthcare

Few films can claim to have directly influenced public policy, but “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest” contributed significantly to the deinstitutionalization movement of the late 1970s and early 1980s. By exposing the dehumanizing aspects of mental hospitals to mainstream audiences, the film helped galvanize support for mental health reform and patients’ rights initiatives.

The character of Nurse Ratched became so emblematic of institutional cruelty disguised as care that her name entered the cultural lexicon. “Ratched” became shorthand for any authority figure who abuses their power while maintaining a veneer of propriety—a characterization powerful enough to inspire a prequel series 45 years after the film’s release.

Within cinema, the film established a new standard for portraying mental illness with complexity and humanity. Moving away from exploitative or simplistic depictions of “madness,” Forman presented patients as fully realized individuals whose conditions were often exacerbated rather than alleviated by their treatment. This more nuanced approach influenced countless subsequent films dealing with mental health themes.

The film’s visual style and narrative structure have influenced generations of filmmakers tackling institutional settings, from prison films like “The Shawshank Redemption” to medical dramas and contemporary examinations of psychiatric care like “Girl, Interrupted.” Its central metaphor—the mental institution as microcosm of society—has become a recurring motif in stories examining social control and rebellion.

The Film’s Legacy: A Perfect Adaptation

“One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest” stands as one of the rare literary adaptations that both honors its source material and succeeds as a standalone cinematic achievement. While Kesey’s novel told its story through Chief Bromden’s hallucinatory perspective, screenwriters Lawrence Hauben and Bo Goldman translated the book’s counterculture message into a more accessible but equally powerful visual narrative.

For Miloš Forman, the film represented a perfect marriage of personal experience and material. Having lived under Czechoslovakia’s communist regime, Forman brought firsthand understanding of institutional oppression to the project, infusing the story with authentic emotional resonance beyond what an American director might have achieved.

Jack Nicholson’s portrayal of McMurphy became the defining role of his career—the culmination of his 1970s antiestablishment persona and the performance against which all his subsequent work would be measured. Similarly, Louise Fletcher’s Nurse Ratched remains one of cinema’s most nuanced villains, avoiding the trap of one-dimensional evil to present institutional cruelty as a human choice rather than simple monstrosity.

Perhaps most significantly, the film’s ending—with its complex mixture of tragedy and qualified triumph—continues to resonate as a statement about the cost of freedom. Unlike conventional Hollywood narratives where good triumphs absolutely over evil, “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest” suggests that victories against oppressive systems often come at terrible personal sacrifice, yet still remain vitally necessary.

Conclusion: A Timeless Examination of Freedom

“One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest” endures not just as a brilliant piece of filmmaking but as a profound philosophical examination of how power operates in society. Through the microcosm of the mental ward, Forman creates a universal story about the human spirit’s resistance to control and the painful, necessary process of breaking free from systems that prioritize order over humanity.

What makes the film particularly remarkable is its resistance to simple moral categorization. McMurphy is no flawless hero—he’s manipulative, selfish, and has committed genuine crimes. Nurse Ratched, despite her cruelty, believes she’s maintaining necessary order. The film acknowledges that both complete freedom and complete control lead to their own forms of destruction, yet ultimately sides with the messy authenticity of self-determination over the sterile safety of submission.

In an era of increasing institutional power—from government surveillance to corporate data collection to algorithmic control of information—the film’s central question remains urgently relevant: What is the proper balance between societal structure and individual freedom? “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest” offers no easy answers but insists we keep asking the question, lest we find ourselves voluntarily committed to systems that diminish our humanity while claiming to protect us.

Did You Know?

- Kirk Douglas originally bought the rights to Ken Kesey’s novel and played McMurphy in a Broadway adaptation, but was too old for the role by the time the film was made

- Director Miloš Forman cast actual mental hospital patients as extras in many scenes

- Louise Fletcher was cast just a week before filming began after several prominent actresses turned down the role of Nurse Ratched

- Ken Kesey was so disappointed with the adaptation that he never watched the completed film

- The production filmed in an actual working mental institution, with the hospital’s superintendent playing the film’s equivalent role

Where to Watch

Available on HBO Max for subscribers and for digital rental or purchase on major platforms including Amazon Prime, Apple TV, and Google Play.

If You Enjoyed “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest,” You Might Also Like:

- “The Shawshank Redemption” (1994) – Another powerful story of institutional life and the human spirit

- “Girl, Interrupted” (1999) – A female perspective on mental institution experiences in the 1960s

- Goodfellas (1990) – For its similarly revolutionary filmmaking approach and examination of individuals fighting against powerful systems

- “Requiem for a Dream” (2000) – A modern examination of institutional treatment and mental health

2 thoughts on “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest (1975) Review: The Revolutionary Classic That Changed Our View of Sanity and Society”